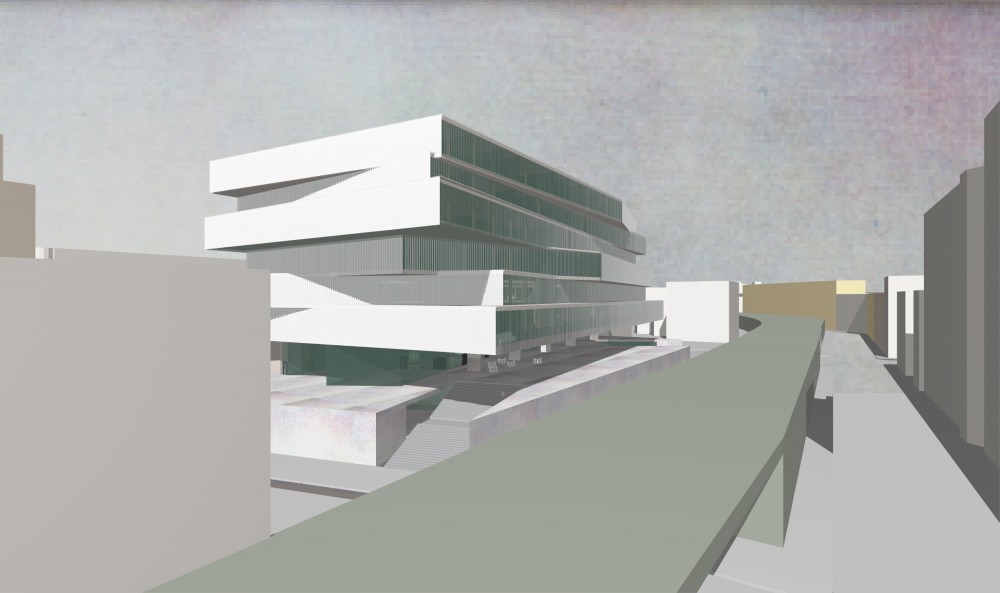

The location of deliberate spatial disorientation

Location // Berlin, Germany

Program // Library

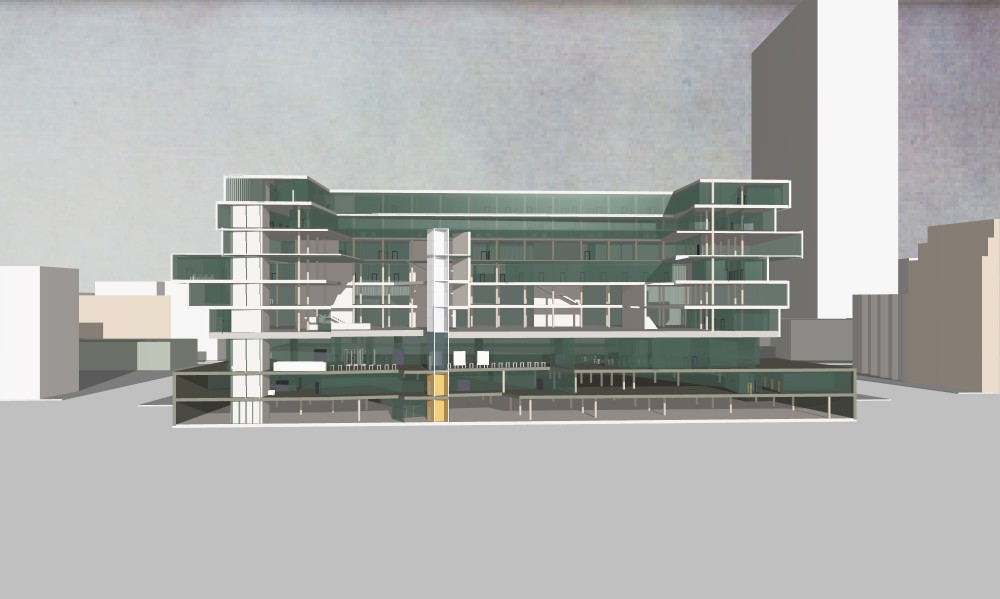

On one hand, it is important that the functions of searching, borrowing, and reading are clear and manageable. On the other hand, the design aims to create labyrinthine spaces of retreat and tranquility that allow individuals to immerse themselves with and within books.

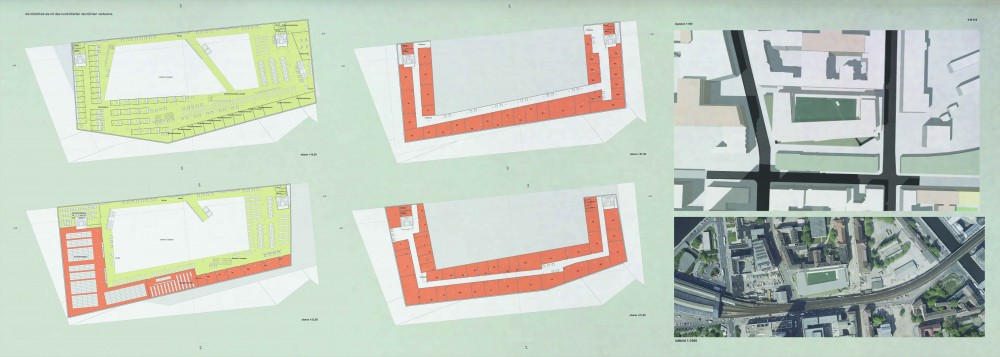

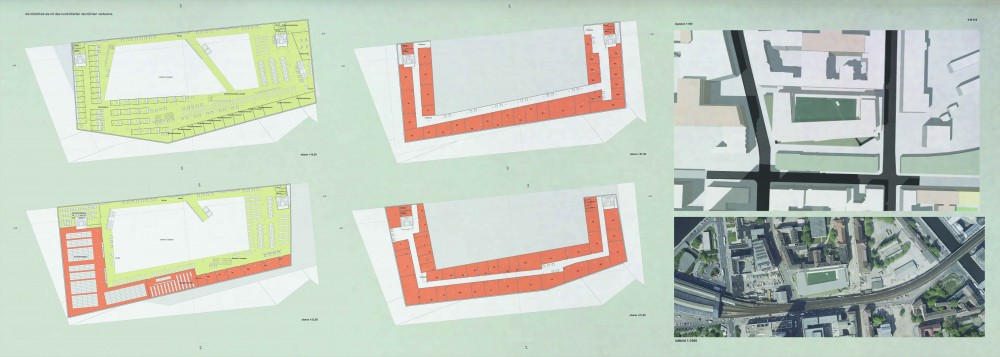

URBAN DEVELOPMENT

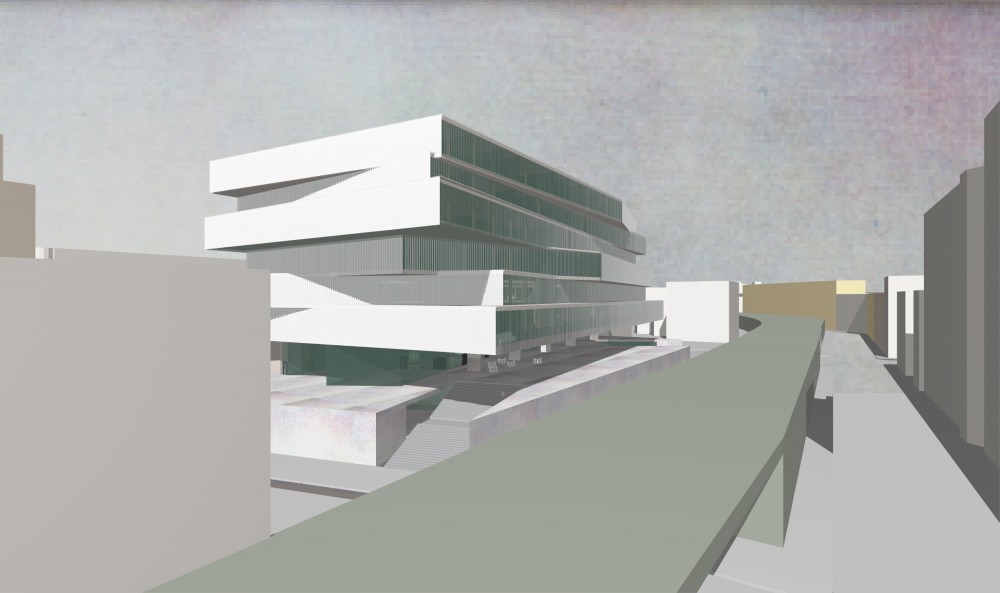

The project adheres to the typical perimeter block development in Berlin. The individual floors shift towards each other, symbolizing a vibrant environment.

FAÇADE

The building features a ventilated climate-controlled double façade with solar-controlled glass louvers. This design provides noise protection from the nearby S-Bahn and reduces heating and cooling energy consumption through rear-ventilation. The shading slats automatically adjust their position based on solar indicators, resulting in a dynamically changing appearance.

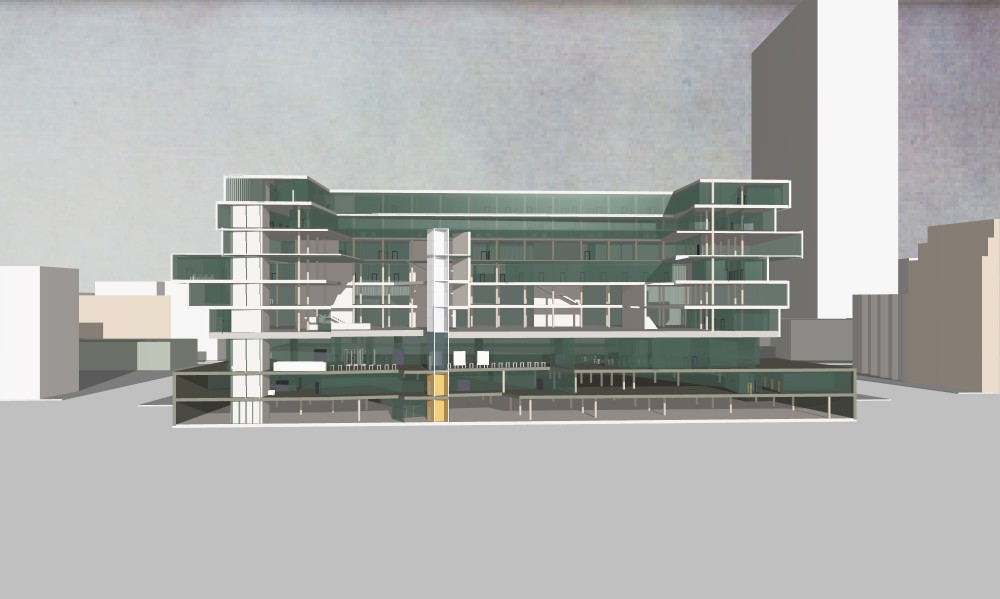

CONSTRUCTION

The structure is built with a reinforced concrete skeleton, utilizing a column grid of approximately 6x6 meters with solid ceilings. The floor slabs are calculated as cantilevers, and the ceiling on the eleventh level is designed as a reinforced concrete slab beam ceiling with a construction height of 100 centimeters. This allows for a support-free terrace level.

"The universe that others call the library is composed of an undefined, possibly infinite number of hexagonal galleries, with wide ventilation shafts in the middle, enclosed by very low railings. First axiom: The library exists ab aeterno. No thinking mind can doubt this truth, from which the future eternity of the world immediately follows. Man, the imperfect librarian, may be affected by chance or malevolent demons, but the universe, with its elegantly furnished shelves, enigmatic volumes, inexhaustible staircases for the wandering librarian, and small steps for the seated librarian, can only be affected by a God. To appreciate the gulf that lies between the human and the divine, one need only compare the shaky marks that my frail hand scrawls on the cover of a book with the organic letters inside: engraved, finely curved, jet black, inimitably symmetrical, they stand there." (Borges 1974, p. 47ff).

On the contrary, I reply, who are we, who is each of us, if not a combination of experiences, information, readings, and fantasies? 'Every life is an encyclopedia, a library, an inventory of objects, a sample collection of styles, wherein everything can be remixed and rearranged in every possible way at any time.'" (Italo Calvino: Six Proposals for the Next Millennium. Munich: Hanser, 1991. 5.165)

What is a library? - If we believe Jorge Luis Borges, it would be the same as the universe, the cosmos, which no one other than a god could have created and whose writing seems inaccessible, incomprehensible to us. So there would be no need to ask about a library at all; all that would remain would be to state: A library is what it is. And that is enough. Seen in this light, it seems presumptuous not only to want to understand a library but also to design it, since this would mean nothing other than doing the same as the Creator and creating a veritable universe from scratch. With all the hubris of the natural sciences of the present, however, this probably demands too much respect from anyone who looks at the starry sky at night to attempt such a thing. And so the exciting attempt to design a library would have to end at this point for lack of its own god qualities, were it not for the ray of hope that Italo Calvino tells us about in his parable of life with a library. If one follows this thought, another dimension of the library appears, apart from its infinity and inaccessibility: it shows itself in its principle thinkability through itself, through our life. For as incomprehensible as we appear to ourselves as human beings, enigmatic, infinite, thrown, to speak with Heidegger, we live, perhaps in a kind of permanent approach to the principally incomprehensible within and before us.

Two things fill the Germüth with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the more often and persistently reflection deals with them: the starry sky above me and the moral law within me. I must not look for both of them as shrouded in darkness, or in the transcendent, outside my circle of vision, and merely suppose them; I see them before me and link them directly with the consciousness of my existence. The first begins with the place I occupy in the outer world of the senses, and extends the connection in which I stand into the incalculably great with worlds and systems of systems, still transcending into boundless times of their periodic movement, their beginning and continuance. The second begins with my invisible self, my personality, and presents me in a world which has true infinity, but is perceptible only to the intellect, and with which (but thereby also at the same time with all those visible worlds) I recognise myself not as there in merely accidental, but general and necessary connection. The former sight of an innumerable multitude of worlds destroys, as it were, my importance as an animal creature that must return the matter from which it was made to the planet <'a mere point in space) after it has been endowed for a short time (one does not know how.) with vitality.

The second aspect, on the other hand, elevates my worth as an intelligence infinitely through my personality. It is through this personality that the moral law reveals to me a life independent of animality and even the entire sensory world, at least to the extent that can be deduced from the purposeful determination of my existence by this law. This law is not confined to the conditions and limits of this life but extends into infinity. (Immanuel Kant: Critique of Practical Reason. 1788. ~ In Academy Edition 1902/10, 5. 161f., unchanged. Reprint: Immanuel Kant: Works in Six Volumes. Vol. 3. Cologne: Könemann, 1995, 5. 480f.) An independent life that transcends the sensory world, surpassing the degradation of pure sensuality, and being completely analogous to the cosmos, it is precisely because of this that it is linked to it with admiration and awe. Is there a more fitting description of an ideal library space? Is this the essence of a library?

We ascended once again to the scriptorium, this time using the wide staircase in the east tower, which also led us to the forbidden upper floor. As I held the lamp high in front of us, I pondered on the words of the aged Alinardus about the labyrinth and prepared myself for the horrors to come. However, to my surprise, when we arrived at the mysterious location, we found ourselves in a moderately sized windowless room with seven walls, permeated by a musty, stale air, much like the rest of the upper floor. There was nothing to be horrified about.

From the novel "The Name of the Rose" by Umberto Eco